How does Internet Peering work in Asia? How is it different from Peering in the U.S. or Europe? If International Peering is different across the globe, what does one need to know before expanding a network into a new country? Internet Peering in Asia has largely been undocumented, with the popular perception in the Internet Operations community that Internet Peering in Asia is “just different”. This research provides a framework for comparing Internet Ecosystems with a little more specificity, based on conversations with about one hundred International Peering Coordinators that have built into and within Asia. These International Peering Coordinators shared ten specific lessons they wish they had learned prior to their Asian expansion.

This White Paper begins by introducing the Internet as a set of loosely connect Internet Ecosystems (countries typically), each with at least three categories of players. We define each category of player, their position in the “Internet Ecosystem” along with their corresponding motivations that explains their peering behaviors.

In the process of the research we identified the “Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic.” This dynamic is not limited to Asia but indeed exists globally, where Tier 1 ISPs in one Internet Peering Ecosystem are relegated to Tier 2 ISPs as they expand into a foreign Internet Peering Ecosystem. We explain why this occurs by applying the aforementioned definitions and motivations.

To apply these definitions and share some of the more interesting country-specific insights shared by the Peering Coordinators, we have identified the key players in four specific Internet Peering Ecosystems; Japan, Singapore, Australia and Hong Kong. We apply the “Business Case for Peering” methodology using current transit and peering costs in each Peering Ecosystem.

We then share five reasons the Peering Coordinators said that they expanded into and within Asia, along with four strategies for interconnecting within Asia. Ten “Lessons Learned” finish up the section of collective knowledge from the group. In this section we also present rough transport/colo/transit pricing figures so the reader can better appreciate the differences in Internet Ecosystems across Asia. This is necessary to understand the financial sides to the peering-transport-transit equation.

(This paper contains time sensitive pricing and operations information, and was written in 2005. Much has changed since this paper was written.)

Introduction: The Global Internet Ecosystem

Peering Inclinations and Peering Policies

The Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic

The Business Case for Peering: Peering vs. Transit

Estimating the Financial Value of an Asia Internet Exchange Point

Asia Pacific Internet Peering Ecosystems We Studied

Hong Kong Peering Ecosystem

Before we can talk about the Asia Pacific Peering Ecosystem, we need to first introduce the Internet as a network of networks, and the Global Peering Ecosystem as descriptive of the interconnection that enables the Internet to work.

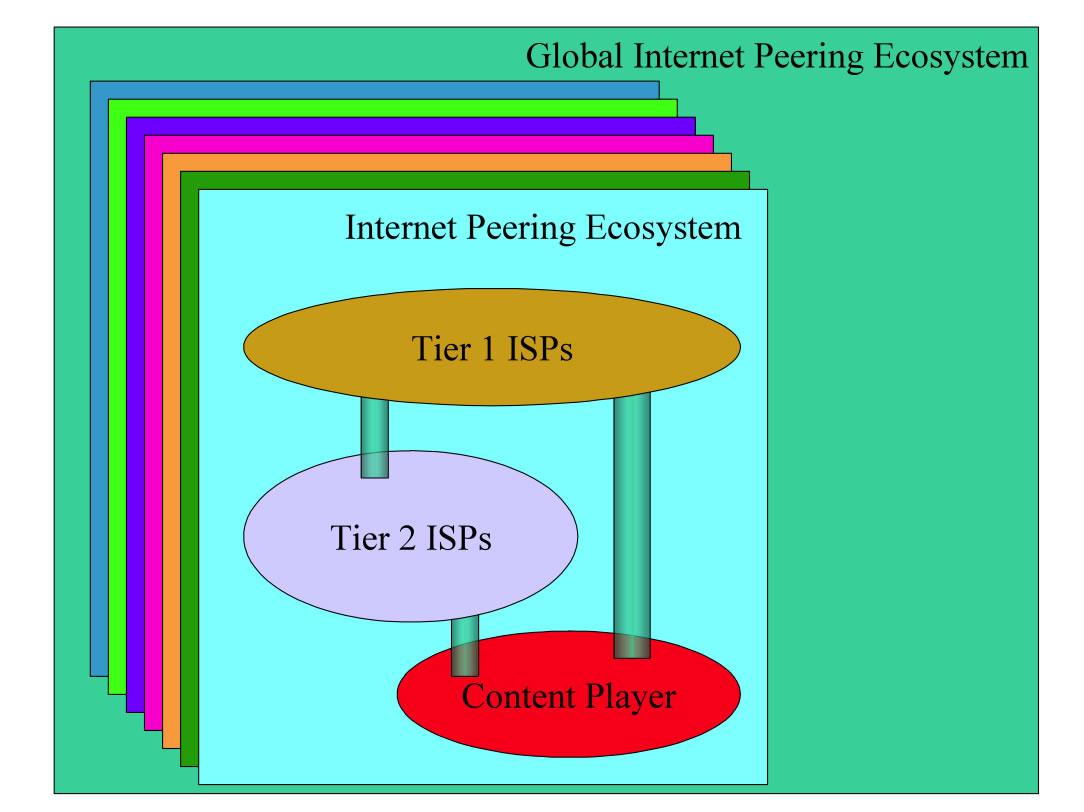

Definition: The Global Internet Peering Ecosystem consists of a set of Internet Regions (loosely bound by country boundaries) that operate an Internet Peering Ecosystem as shown below.

An Internet Operations view of this system reveals categories of players, each with motivations and observed behaviors in common within geographical areas that I will call Internet Peering Ecosystems.

Within each of these Internet Peering Ecosystems we find at least three categories of players: Tier 1 ISPs, Tier 2 ISPs and Content Providers. We will go through each in turn.

Definition: A Regional Tier 1 ISP is an ISP that has access to the entire Internet Region routing table solely through Peering relationships.

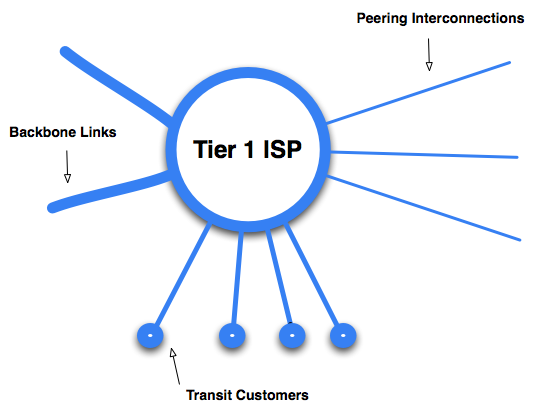

The figure above models a Tier 1 ISP graphically as selling transit to downstream customers, peering traffic away off to the side, and operating backbone links to offload the traffic elsewhere in their network.

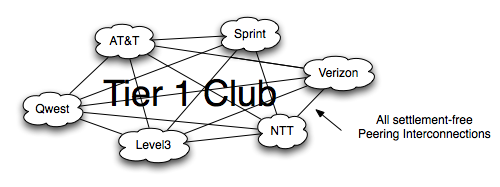

Through these free peering connections, the Tier 1 ISPs all enjoy settlement-free access to all destinations within the Internet Region. Some in the Peering Community refer to the set of Tier 1 ISPs as the "The Tier 1 club". The Tier 1 ISPs sell access to the region as part of a transit service as well, often as a wholesale transit service, to Tier 2 ISPs, CDNs, and Large Scale Network Savvy Content Providers.

While this "Tier 1 ISP" definition has been criticized as being almost impossible to prove it is an important distinction as it pertains to ISP motivations and behaviors in the Internet Region. Tier 1 ISPs are not motivated to peer to reduce the cost of transit since, by definition, Tier 1 ISPs don’t pay for transit.

Tier 1 ISPs may peer in many geographically diverse locations for technical reasons. Peering has the benefit of lower latency, better control over routing, and may therefore lead to lower packet loss. For ISPs that charge on a per-Mbps basis, this leads to financial benefits as customers use more bandwidth and therefore pay more money. This is a function of TCP: lower latency and lower packet loss means that the TCP window opens more quickly. This results in greater usage and therefore greater customer revenue. Most Tier 1 ISPs around the world exchange enough traffic with each other to require multiple points of interconnect.

A Tier 1 Peering Policy generally includes a minimum number of locations as a requirement for peering.

Tier 1 ISPs do not need to buy transit since by definition they can reach all the networks in the Internet Peering Ecosystem solely through free peering relationships. Stated most eloquently by Waqar Khan (Qwest, a Tier 1 ISP in the U.S.), “We have all the peering we need.” It is not surprising that Tier 1 ISPs see the rest of the players in the Internet Peering Ecosystem players as potential customers, and do not seek peering with them. In fact, James Spenceley (Comindico) went through the process of negotiating peering with the Tier 1 ISPs in Australia and described the Tier 1 peering negotiation tactics in a one word acronym: MILD: Make It Long and Difficult . This reflects the ISP’s underlying Peering Inclination, perhaps articulated in their Peering Policy .

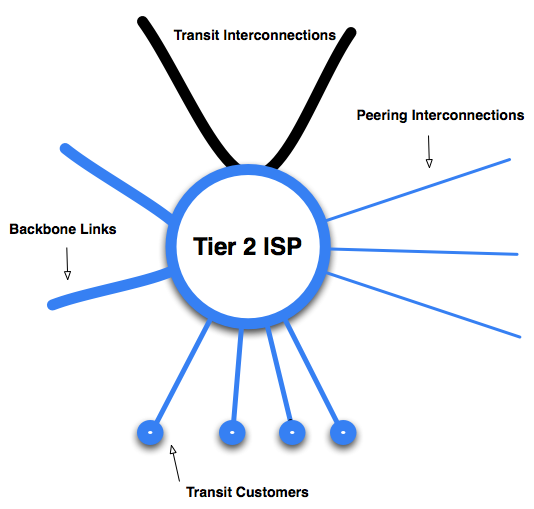

The figure above models a Tier 2 ISP graphically position as purchasing transit from an upstream provider, selling transit to downstream customers, peering traffic away off to the side, and operating (optional) backbone links to offload the traffic elsewhere in their network.

A Tier 2 ISP will often embrace peering to reduce transit costs, improve performance, and potentially even increase revenue. You will find Tier 2 ISPs participating actively in Peering Forums - this is an expected bahavior from a player looking to increase the amount of peering they have. Some of the larger Tier 2 ISPs will be able to peer away towards 70% of their traffic.

Definition:

Content Providers are all companies that operate an Internet Service but do not sell transit within the Internet Peering Ecosystem.

The model above shows this player simply purchasing transit from an upstream provider while creating content as their core business.

These rough classifications and definitions are important because they help us understand each player’s motivations as reflected in their observed behavior.

We can explain an ecosystem participant's Peering Behavior by identifying their position and corresponding Peering Inclination as articulated in the form of a Peering Policy .

Definition: A Peering Inclination is a predisposition towards or against peering as demonstrated by Peering behavior in an Internet Peering Ecosystem.

Definition: A Peering Policy is an articulation of the Peering Inclination; it documents and defines the prerequisites to peering.

Our research has identified four categories of peering policies:

Definition: A Restrictive Peering Policy is an articulation of an inclination not to peer with any more entities.

A Tier 1 ISP may have a posted peering policy indicating that they will peer with ISPs of similar size and scale that meet them in a large number of locations in a certain number of countries with a certain large traffic volume. In this research, several Tier 2 ISPs have expressed frustration that once they met these stated requirements, the requirements were immediately adjusted upwards just out of reach. This demonstrates the Restrictive Peering Policy underlying foundation - an inclination not to peer.

Definition: A Selective Peering Policy is an articulation of an inclination to peer, but with some conditions.

A Selective Peering Policy details prerequisites that must be met, and when met, will generally lead to peering. Some ISPs for example require multiple interconnect points across a country with a minimum amount of traffic in order for it to be worth the engineer’s time to set up the peering session. Large Tier 2 ISPs often have Selective Peering Policies; they want to peer, but have a threshold to pass in order for it to be worthwhile. The difference between the Selective and the Restrictive peering policy is somewhat subjective but is based on the underlying intent; a restrictive peer does not want to peer with anyone else so sets requirements arbitrarily high such that almost no one is qualified to peer with them.

Definition: An Open Peering Policy is an articulation of an inclination to peer with anyone.

Brokaw Price from Yahoo! calls this “pulse peering; if you have a pulse we will peer with you!” Content Players and most Tier 2 ISPs seek to reduce their transit fees by peering broadly by announcing to the peering community that they have an Open Peering Policy.

While these broad categories of players and their peering policies do not capture all facets of the markets, they do provide the broad strokes needed to understand some of the International peering interplay that we will discuss in this paper.

Definition: A No-Peering Policy is an articulation of an inclination not to peer at all.

Those with a no-peering policy simply do not see peering as an important strategy for for them to employ to get connectivity to the global Internet.

The rest of this paper focuses on several Asia Pacific Peering Ecosystems. First we will start with some observations common across ecosystems - for example, the challenge Tier 1 ISPs have when expanding into a new ecosystem. We call this the "foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic". We then work through the Peering Break Even point and the Peering vs Transit analysis to set up the discussion surronding Peering Ecosystems across Asia.

Specifcally, we finish this section with an overview of four Internet Peering Ecosystems: Japan, Singapore, Australia and Hong Kong, highlighting the key players, recent trends and disruptions in the peering ecosystems, and the Business Case for Peering in each Peering Ecosystem using recent prices for transport, transit, collocation and Exchange Point fees.

Editor’s Notes: To illustrate points made in this paper we polled people for estimated prices of local loops, transit, transpacific transport, etc. All prices shown are in U.S. Dollars (unless otherwise indicated), and should be assumed to be volatile and for illustration and comparison purposes only.

Sources and Notes ...

Some International ISPs described the Asia Pacific Peering Ecosystems as “mysterious”, with the only discernable behaviors exhibited being those of protection of the domestic market.

“Protection of turf is much stronger in Asia than in the U.S. or Europe.” – Large European ISP

Conversations with both in-country and foreign Peering Coordinators however reveal that there are two sides to this story. This interplay is described next as the “Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic.”

Definition: The Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic occurs when a Tier 1 ISP in one Internet Peering Ecosystem expands into another Internet Peering Ecosystem and is relegated to a Tier 2 ISP status in that foreign Internet Peering Ecosystem.

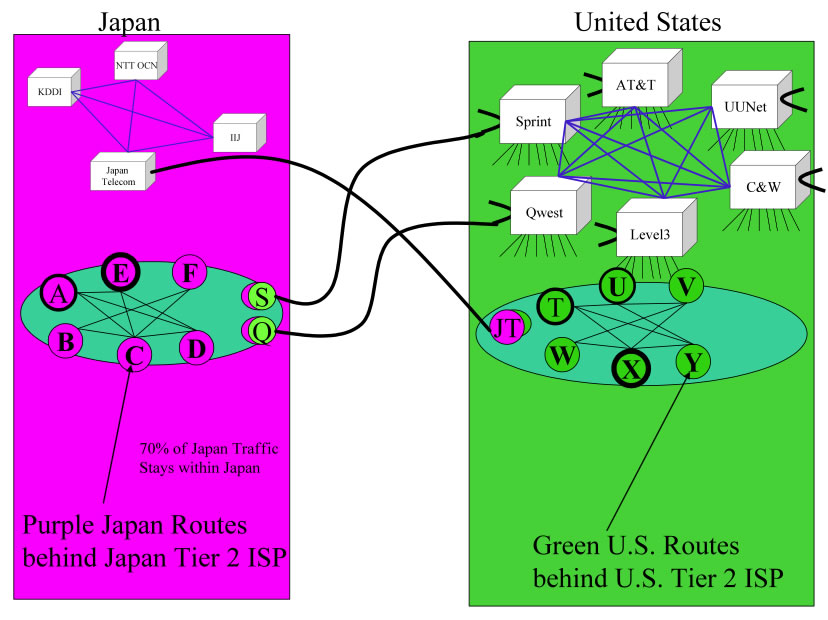

This dynamic is illustrated in the example figure below, where UUNet (a Tier 1 ISP in the U.S.) expanded into Japan in the mid-1990’s.

Figure 2 - Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic

To demonstrate this dynamic, consider this Peering Coordinator’s story. Several years ago over a dinner in Tokyo, the author was told that “UUNet is one of the largest ISPs in the world, but we can’t get peering with any of the Tier 1 ISPs here in Japan, and have a hard time even getting Peering with the Tier 2 ISPs!”

What is going on here?

Understanding the Request for Peering with the Foreign Tier 1 ISP. In this scenario, when UUNet asks the Japanese Tier 1 ISP to peer, it is asking the Japanese Tier 1 ISP to

It is understandable that the in-country Tier 1 ISP (like NTT) would not be motivated to peer with a foreign ISP (like UUNet) entering the market. It would take something very large in return for this play to make sense to the in-region Tier 1 ISP.

Global Routes or Regional Routes? At the same time, UUNet may not want to peer all of its U.S. and European routes and

As a result the UUNet negotiating position is likely to be that they will only bring their Asia Regional routes for peering in Japan, and not their large number of desirable U.S. and European customer routes. Since peering NTTs relatively large number of routes with UUNets relatively small number of regional routes doesn’t make business sense for NTT, the deal is unlikely to go through.

In some cases, the discussion of “reciprocal in-country peering” comes up (you peer with me in your country and I’ll peer with you in mine), but the negotiations often get mired in definitions and perceptions of “equal benefits”. It is not surprising that these reciprocal peering deals don’t occur very often.

To continue with our example, in this scenario, UUNet also has difficulty getting peering with the Tier 2 ISPs. Let’s look at the incentive/disincentive for the Tier 2 ISPs to peer with this foreign (U.S.-based) Tier 1 ISP.

In-Country Tier 2 Peering with Foreign Tier 1 ISP. Tier 2 ISPs are motivated to reduce transit costs, but in the case of Japan, as with many parts of Asia, only a small percentage (5% ) of its traffic is destined to and from the U.S. Only those Tier 2 ISPs with enough Japan-U.S. traffic have sufficient financial motivation to accept peering. If UUNet doesn’t provide U.S. routes, then there may not be enough of a UUNet Japan customer base footprint to make them a strong peering player.

There are of course other motivations for peering. For example, performance related improvements may be sufficient for some Japanese Tier 2 ISPs to peer with the foreign Tier 1 ISP. Also, for some ISPs, turning up peering is an easy task so they adopt an “Open” policy. For them, UUNet simply has to interact with the right person at the right time in the right language.

The Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic is observed in the other direction as well; Japan Telecom is peering in the U.S. with a subset of the Tier 2 ISPs, with little luck getting peering with the Tier 1 ISPs.

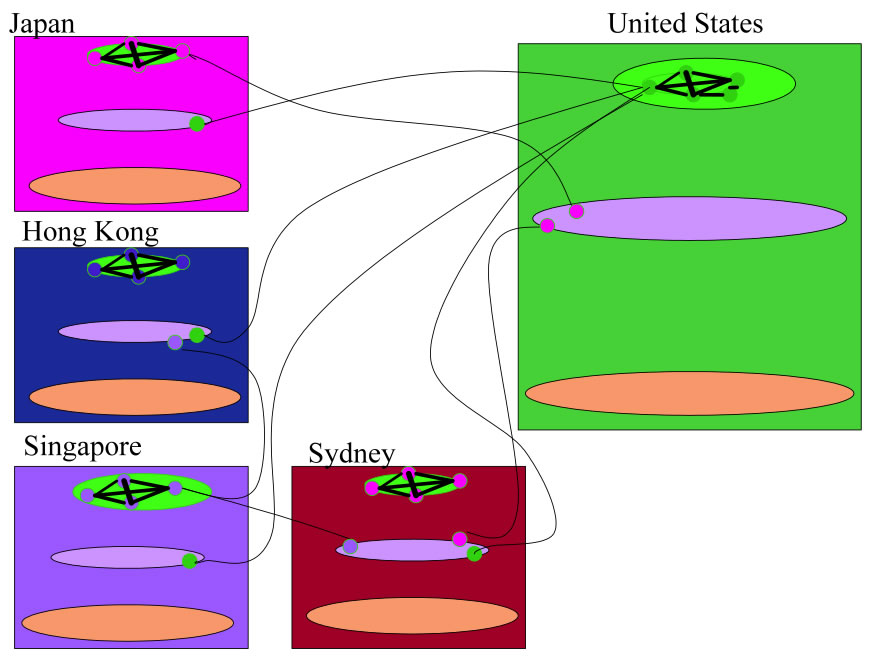

The Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic is seen Globally. If we illustrate this dynamic this across several Internet Peering Ecosystems, we see the effect as shown in the diagram below. With the exception of NTT/Verio, who acquired Tier 1 status in the U.S. Internet Peering Ecosystem through acquisition of Verio, few Tier 1 ISPs have been able to successfully build in and reach Tier 1 status in a foreign country. (Those that did used some combination of the tactics documented in “The Art of Peering: The Peering Playbook”, freely available from the author.)

Figure 3 - The Generalized Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic

We found one notable exception to the Foreign Tier 1 Peering Dynamic in mainland China. Both China Telecom and China Netcom, the two Tier 1 ISPs in China, have signaled their preference to openly peer their routes with foreigners, and do so in China! The stated motivation was to reduce costs of accessing the rest of the Internet, and to demonstrate openness as they deregulate the China Telecommunications sector. They would prefer not to pay the cost of backhauling all the Internet traffic for all of its customers back to China. It remains to be seen if China Telecom’s Asia Pacific Internet Exchange (APIX) concept in Shanghai takes off.

Sources and Notes ...

Note that much of the traffic is pulled from the U.S. Much of this traffic is pornographic content, or to be politically correct, is “Content that transcends the language barrier.” By law, this content may not be hosted in Japan.

There was a similar problem in the U.S. Internet during the NSFNET era (1987-1994) when much of the U.S. government-funded Internet capacity from Europe was used up with traffic of this type.

Conversation with Fumio Terashima (Japan Telecom). Note that the total volume of traffic still is about 3Gbps as of June 2003

We are using the same methodology follow in the Business Case for Peering white paper previously released.

Assuming that performance is not an issue with the upstream provider.

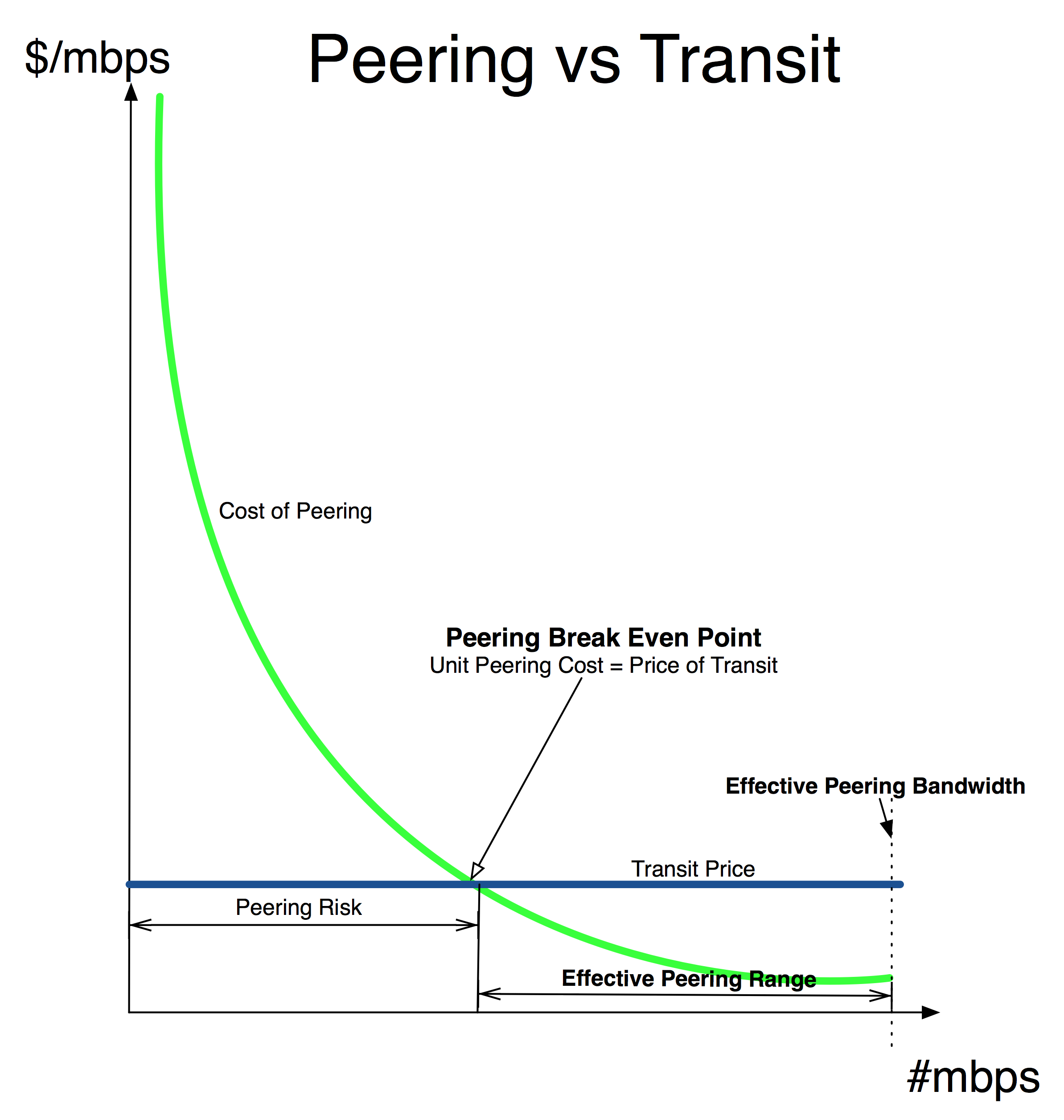

We will make the Business Case for Peering in each of these Peering Ecosystems. We do this by comparing the cost of peering against the unit cost of buying transit . First we plot the cost of peering at an exchange point against the amount of traffic peered. We then plot the transit cost and find the intersect point, called the Peering Breakeven Point.

Definition: The Peering Break Even Point is the point where the unit cost of peering exactly equals the unit cost for transit.

We cap the peering at the Effective Peering Bandwidth, which is the maximum bandwidth available for peering after taking into account layer 2 framing and port limitations. Then we can compare the cost of peering against the cost of transit, taking into account all costs of peering (except for equipment costs).

When it costs less to send traffic to an upstream transit provider, ISPs should rationally prefer to do so . When the unit cost of sending traffic to an IX is less, ISPs should prefer to use an IX to offload this transit traffic. Beyond the Peering Breakeven Point, all peering costs (circuit into the IX, router, rack, port fees) are completely covered by the cost savings of peering. This is shown in the figure below, highlighting a few points of interest to the Peering Coordinator community.

Over the past few years, transit prices have dropped dramatically, sending the breakeven point out and to the right. One needs to peer more traffic these days for peering to make sense. We will apply this framework to find the business case for peering in each Peering Ecosystem.

Sources and Notes ...

Note that much of the traffic is pulled from the U.S. Much of this traffic is pornographic content, or to be politically correct, is “Content that transcends the language barrier.” By law, this content may not be hosted in Japan. There was a similar problem in the U.S. Internet during the NSFNET era (1987-1994) when much of the U.S. government-funded Internet capacity from Europe was used up with traffic of this type. Conversation with Fumio Terashima (Japan Telecom). Note that the total volume of traffic still is about 3Gbps as of June 2003 We are using the same methodology follow in the Business Case for Peering white paper previously released. Assuming that performance is not an issue with the upstream provider.

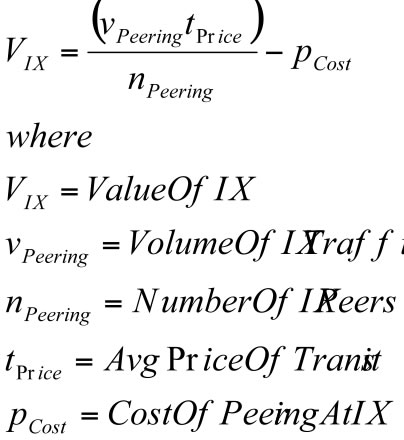

Definition: The Financial Value of an Internet Exchange is a measure of the financial value derived from an IX by its participants. It can be estimated by subtracting the collective cost of participation from the collective benefits of participation (sending that peering traffic over a transit service instead).

Let’s start the analysis by making a three simplifying assumptions.

First, the value an Internet Exchange point provides is facilitating the peering of traffic between participants. There are at least two dimensions to the value of peering: the value of the traffic volume peered, and the routes announced at the IX. We will only focus here on valuing the volume of traffic in this article; the routes announced deserves its own analysis.

Second, it is important to note that several large IXes have both public peering fabrics and private peering services. Private peering is traffic directly exchanged between two parties, often over a physical piece of fiber or a virtual private service. Being able to do both public and private peering represents a significant value of the IX, but unfortunately the traffic peered privately can’t be factored into the analysis since there is no visibility into the amount of traffic exchanged privately. For this reason, we will have to start out with the simplifying assumption that the value of the IX is proportional only to the value of public peering. (The LINX has migrated some large traffic flows onto private peering so as a result this analysis will consequently understate their value.)

Third, let’s assume that the alternative to peering is buying transit, so the value of the IX can be estimated to be

MarketTransitPrice * VolumeOfTrafficPeered

for free at the IX.

Under these assumptions, if the IX went away, the community using the IX would have to exchange that traffic with their transit provider at a metered rate. We further assume that the IX peak measure approximates the 95th percentile measure upon which transit is billed.

We say ‘peered away for free’, but public peering is not completely free. The cost of public peering includes some monthly recurring costs for each participant at the IX. If we subtract these costs from the value derived, we can estimate the value of the IX to the population:

ValueIX = TrafficPeeredAtIX * TransitPrice – CostOfPeering*NumberOfMembers

Observation: The Internet Exchange Points exhibit the characteristics of what economists call the “Network Externality Effect”; the value of the product or service is proportional to the number of users of the product or service .

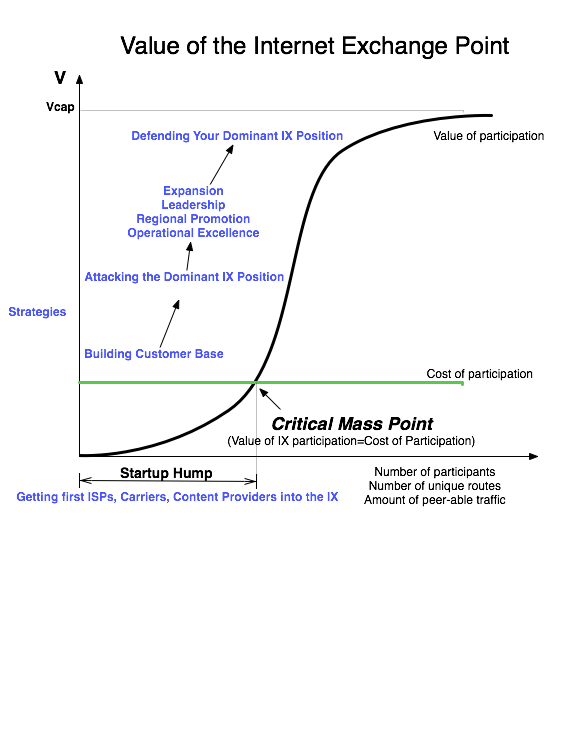

Internet Exchanges are a special case of this effect; the value of an Exchange Point is not the number of participants but a slightly more complex calculation including the number and uniqueness of the routes and volume of traffic peered. Since the value of the IX to an ISP is proportional to the amount of traffic the ISP can exchange in peering relationships at the IX, the value of the IX to the peering population follows the network externality graph as shown below.

On the Y-axis we see the value of the Internet Exchange Point. On the X-axis we see the independent variable that causes the value of the IX to increase; we will use the number of participants for now; as more participants connect to the exchange for peering, the more value an NSP could derive from peering at the IX

All Internet Exchange Points go through the following growth curve. They start out with zero or a few founding ISP members, and face the challenge of attracting additional peers into a building where there are not many peers to peer with. This is the "startup hump", and solutions to this problem were shared with the author in "The Art of Peering: The IX Playbook".

Once the IX reaches critical mass, where the value of participation exceeds the cost of participation, the a well positioned IX experiences exponential growth.

Note: Some variables in this equation may be difficult to obtain.

Many Internet Exchange Points make the aggregate peering traffic volume available to the public, but some do not.

Further, private peering exchanges often utilize cross connects making it impossible to assess the total amount of traffic traversing their private exchange. This formula is therefore more accurately described as the value of a Public Internet Exchange fabric to the participants. To calculate the value of the Internet exchange, one would need to include not only the public peering fabric, but also the benefits of private peering and buying/selling transit in an environment where interconnection cross connects is less expensive than with local loops.

Be sure to chaeck out the Modeling an Internet Exchange Point for a list of the assumptions in this model.

Now we can estimate the value of the Internet Exchange Point, or at least the value of the public peering that we can measure at the Internet Exchange Point.

Sources and Notes ...

Hong Kong Peering Ecosystem

Internet Transit Pricing Historical and Projections

Index of other white papers on peering

WIlliam B. Norton is the author of The Internet Peering Playbook: Connecting to the Core of the Internet, a highly sought after public speaker, and an international recognized expert on Internet Peering. He is currently employed as the Chief Strategy Officer and VP of Business Development for IIX, a peering solutions provider. He also maintains his position as Executive Director for DrPeering.net, a leading Internet Peering portal. With over twenty years of experience in the Internet operations arena, Mr. Norton focuses his attention on sharing his knowledge with the broader community in the form of presentations, Internet white papers, and most recently, in book form.

From 1998-2008, Mr. Norton’s title was Co-Founder and Chief Technical Liaison for Equinix, a global Internet data center and colocation provider. From startup to IPO and until 2008 when the market cap for Equinix was $3.6B, Mr. Norton spent 90% of his time working closely with the peering coordinator community. As an established thought leader, his focus was on building a critical mass of carriers, ISPs and content providers. At the same time, he documented the core values that Internet Peering provides, specifically, the Peering Break-Even Point and Estimating the Value of an Internet Exchange.

To this end, he created the white paper process, identifying interesting and important Internet Peering operations topics, and documenting what he learned from the peering community. He published and presented his research white papers in over 100 international operations and research forums. These activities helped establish the relationships necessary to attract the set of Tier 1 ISPs, Tier 2 ISPs, Cable Companies, and Content Providers necessary for a healthy Internet Exchange Point ecosystem.

Mr. Norton developed the first business plan for the North American Network Operator's Group (NANOG), the Operations forum for the North American Internet. He was chair of NANOG from May 1995 to June 1998 and was elected to the first NANOG Steering Committee post-NANOG revolution.

William B. Norton received his Computer Science degree from State University of New York Potsdam in 1986 and his MBA from the Michigan Business School in 1998.

Read his monthly newsletter: http://Ask.DrPeering.net or e-mail: wbn (at) TheCoreOfTheInter (dot) net

Click here for Industry Leadership and a reference list of public speaking engagements and here for a complete list of authored documents

The Peering White Papers are based on conversations with hundreds of Peering Coordinators and have gone through a validation process involving walking through the papers with hundreds of Peering Coordinators in public and private sessions.

While the price points cited in these papers are volatile and therefore out-of-date almost immediately, the definitions, the concepts and the logic remains valid.

If you have questions or comments, or would like a walk through any of the paper, please feel free to send email to consultants at DrPeering dot net

Please provide us with feedback on this white paper. Did you find it helpful? Were there errors or suggestions? Please tell us what you think using the form below.

Contact us by calling +1.650-614-5135 or sending e-mail to info (at) DrPeering.net